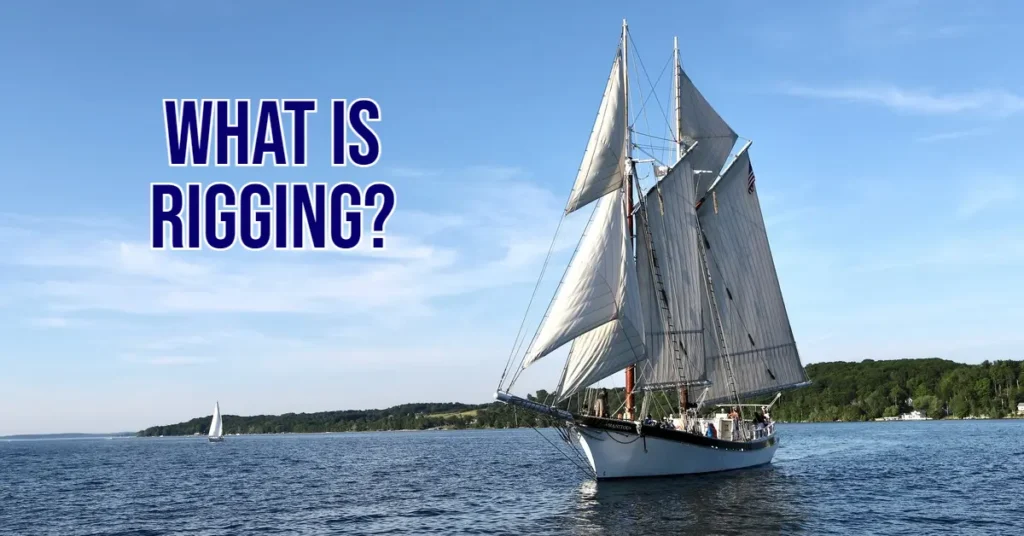

Rigging has been an essential part of preparing vessels for travel since the invention of the first sailboat. The word is both a noun and a verb, meaning “clothing” or “to clothe” in old Anglo-Saxon. Sailors must put all the ship’s components in place before setting sail. It doesn’t matter if they’re operating a small recreational boat or a massive commercial vessel.

For today’s container ships, rigging revolves around loading and securing essential equipment and cargo, while rigging for classic sailboats deals with the sails. Here’s more on the rigging process of modern and traditional ships.

Rigging Modern Ships

The rigging of modern container ships involves loading and securing equipment and cargo before transport. Every vessel has a unique rigging plan that shipyard workers or “riggers” must follow with utmost precision.

A rigging plan is basically a blueprint for lifting and securing heavy loads onto the ship. This blueprint includes the positions, sizes and safe working loads (SWL) of the deck eye plates, runners, guys, twist locks, wedges, chocks, beams, preventers and shackles. Many of these parts are found on traditional sailing ships and play the same role of keeping equipment steady.

Most commercial ships today have all the equipment they need already on board. As such, shipping companies try to avoid unrigging the equipment to improve their shipping efficiency and save more time between voyages. However, they still require rigging when loading fresh cargo or if something needs to be repaired or replaced.

The shackles — also known as “gyves” — are the key pieces of the rigging puzzle. They are responsible for connecting the crane or forklift to the load, which means they must be durable. Industrial shackles used for shipping, manufacturing and other industrial applications are made exclusively of steel, whether galvanized, alloy, carbon or stainless.

Cranes and front-loading and side-loading forklifts are the primary machines used to load cargo, but sometimes specialized machinery is required. Riggers might have to use top handlers, side handlers, straddle carriers, reach stackers or radial telescopic shiploaders. The bigger the ship, the more vehicles are usually required.

As the riggers load the equipment on board, they may have to redistribute the weight so the ship doesn’t lean too far in any direction. One common example of weight redistribution is trimming, in which the riggers shift around dry bulk cargo to help the vessel remain balanced. They may also use different stacking techniques when loading containers on top of each other.

The final step in the rigging process is inspecting the newly repaired or added parts. Inspectors may put the components through nondestructive testing to ensure they meet industry standards and the vessel’s specifications. The crew must also confirm that every piece of cargo or equipment not directly attached to the ship is secure.

Rigging Traditional Sailing Ships

While rigging is a verb when referring to modern cargo and container ships, it becomes a noun when referencing traditional sailing ships. A vessel’s rigging consists of the ropes, cables, and chains that support and control the masts and sails. Preparing these parts for a long voyage involves various tasks depending on the vessel’s size and shape.

For older square-rigged boats, the sails are rigged from side to side. For newer boats, the sails are rigged from front to back — also known as fore-and-aft. Ships with fore-and-aft rigs quickly became the most common option once sailors realized the triangular sails could point higher into the wind and offered more maneuverability.

One or two experienced people can easily assemble a sailboat’s rigging for personal use. The first task is to install the rudder, which is the steering apparatus that attaches to the stern. The next attachment is the tiller, a long, thin steering arm that connects to the rudder for better control.

With the rudder and tiller in place, it’s time to focus on the sails. Unlike modern cargo ships that can keep all their equipment on board, sailboats must have their sails removed after each voyage to avoid getting damaged. Putting the sails back on the boat is called “bending on” because the crew must bend them into place.

The next item that gets attached is the jib halyard shackle, which connects to the top corner of the sail or the head. The grommet attaches to the front bottom corner of the sail, also known as the tack. The grommet and tack are then shackled to the fitting at the bottom of a piece of standing rigging called the forestay.

The next step’s difficulty largely depends on the wind. If it’s a calm day, one person can easily attach the jib halyard to the forestay. This step is called “hanking” because you need to clip the hanks — the spring-loaded iron rings that keep the sales in place — onto the forestay. There must not be any twists or creases in the sail as it slowly gets raised into position.

When all the hanks are attached to the forestay, the jib sheets are secured to the sail’s clew. All these preparations are required before rigging the mainsail. The mainsail connects to the main halyard, which is almost the same as attaching the jib halyard. The main halyard also serves as a topping lift on smaller sailboats to keep the mast’s boom in place.

The mainsail gets secured to the boom at three points — the luff, clew and foot. The luff is the leading edge, the clew is the front lower corner and the foot is the bottom edge. For some boats, the foot doesn’t attach to the boom and instead gets drawn tightly so it doesn’t move. These boats are called loose-footed sailboats.

Finally, the mainsail is attached to the mast with a bolt rope or “slugs” that are evenly spaced on the luff. Continue raising the mainsail and inserting each slug. When the mainsail is all the way up, pulling on the halyard creates more tension in the luff and keeps the sail in place. Then, the halyard gets tied to the cleat hitch so everything is secure.

As evidenced by the complex terminology and detailed steps, rigging a full-size sailboat for commercial use is a lot of work. Plus, the crew must account for the ship’s unique sail structure. Sailboats can have multiple types of rigging that require special steps for assembly. Here’s a detailed breakdown.

- Standing Rigging

Standing rigging refers to the lines, wires and rods that remain in a fixed position. These components are almost always located between the mast and main deck. Their tension helps the mast stay in place and prevents it from swaying. Standing rigging used to be made of tar-coated rope, but today, it’s made of steel cables.

- Running Rigging

Running rigging includes the cordage that controls the sails’ positioning. The halyards raise the sails and regulate their tension, while the outhaul, downhaul and clew regulate the sail’s shape. Sheets and braces control the sail’s orientation to the wind. Manilla rope was historically the material of choice, but now ropes with synthetic fibers are more common.

- Sloop Rigging

Sloop rigging consists of a single mast with a triangular mainsail and jib. It’s a common arrangement on sailboats from small dinghies to large commercial cruisers. Beginner sailors often choose boats with slope rigging because of their simple layout. It dates back to the 1600s when European sailors perfected the design.

- Cutter Rigging

Cutting rigging has a similar layout to sloop rigging, but it has an additional headsail that provides extra control over speed and direction. The headsail is smaller than the mainsail and jib so one person can control it if necessary. It’s a great choice for longer voyages and journeying through heavy winds.

- Ketch Rigging

Ketch rigging consists of two masts instead of one, which is common on larger sailboats. The main mast is standard size, but the mizzen mast near the rudder is smaller. Both are triangular in shape. Ketch rigging is highly versatile because the sail connected to the mizzen mast can be taken down if necessary.

- Yawl Rigging

Yawl rigging is similar to ketch rigging, but the mizzen mast is closer to the bow for more control. The slight change in mast location offers more control over the boat’s direction in heavy winds. Again, the mizzen mast’s sail doesn’t have to be used. The crew can always lower it and effectively return to a sloop rigging design without missing a beat.

There are many other outdated or little-used rigging types, including lateen, gaff, junk, gunter, settee and crab claw rigging. These configurations are no longer popular for one of two reasons. Either they utilized square sails instead of triangular sails or they relied on freestanding masts, which are unstable without extra standing rigging.

Rigging Comes in Many Forms

Rigging comes in many forms. It means something entirely different for modern cargo ships and traditional sailboats. For engine-powered vessels, rigging refers to the loading and securing of equipment. For sailing ships, rigging refers to the various ropes, cables and other devices that connect the masts and sails. In both cases, many subcategories and technical terms are underneath the surface.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does rigging mean?

Rigging can mean several things depending on the vessel in question. For modern engine-powered ships, rigging simply means loading and securing equipment or cargo. For traditional sailboats, rigging means the various components that connect the sail and mast and allow the boat to navigate.

What is the rigging process of a cargo ship?

Rigging a cargo ship includes a plan that maps out all the ship’s components that hold equipment or cargo in place. Shipyard workers, or riggers, load the equipment to the plan’s exact specifications and utilize different storage or weight distribution methods. The final step is an inspection, which may include nondestructive testing for compliance.

What is the rigging process of a sailboat?

The rigging process of a sailboat has many more steps. For a simple vessel, the crew has to install or connect the rudder, tiller, jib and mainsail. Each part requires careful precision because the sails can’t be twisted, creased or unstable.

Which sails are best for rigging?

Historically, square sails were the most popular ones to rig on ships. However, triangular sails have become the dominant shape because they can catch the wind at a higher point, giving the crew more control over the vessel.

What are the different types of rigging?

There are many different types of rigging. For starters, every sailboat has standing and running rigging. Standing remains stationary, while running moves around and controls the positions of the sails. Other common types include sloop, cutter, ketch and yawl.

- The 15 Most Exciting New Ships of 2025 – January 6, 2025

- How Old Do You Have to Be to Drive a Boat? – November 12, 2024

- The Engineering Behind Ice-Class Vessels – September 20, 2024