Have you ever wondered about a ship’s weight or encountered terms like gross tonnage, net tonnage, displacement, and lightship weight? This guide clarifies these concepts, explaining what ship tonnage truly means, its history, and its importance in modern shipping.

What is Ship Tonnage in Shipping?

Ship tonnage refers to the carrying capacity of a vessel, measured by volume or weight. In modern shipping, tonnage often indicates the total registered tons or the ship’s capacity. The concept of tonnage originated to calculate duties or taxes, initially based on the internal volume of ships.

Today, tonnage plays a crucial role in:

- Regulations and fees: impacting crew rules, port fees, and registration costs.

- Safety standards: determining safety protocols based on the size and type of vessel.

Key Note: Tonnage measurement now often relies on weight, marking a shift from the earlier volume-based methods.

What Are The Different Types Of Ship Tonnage?

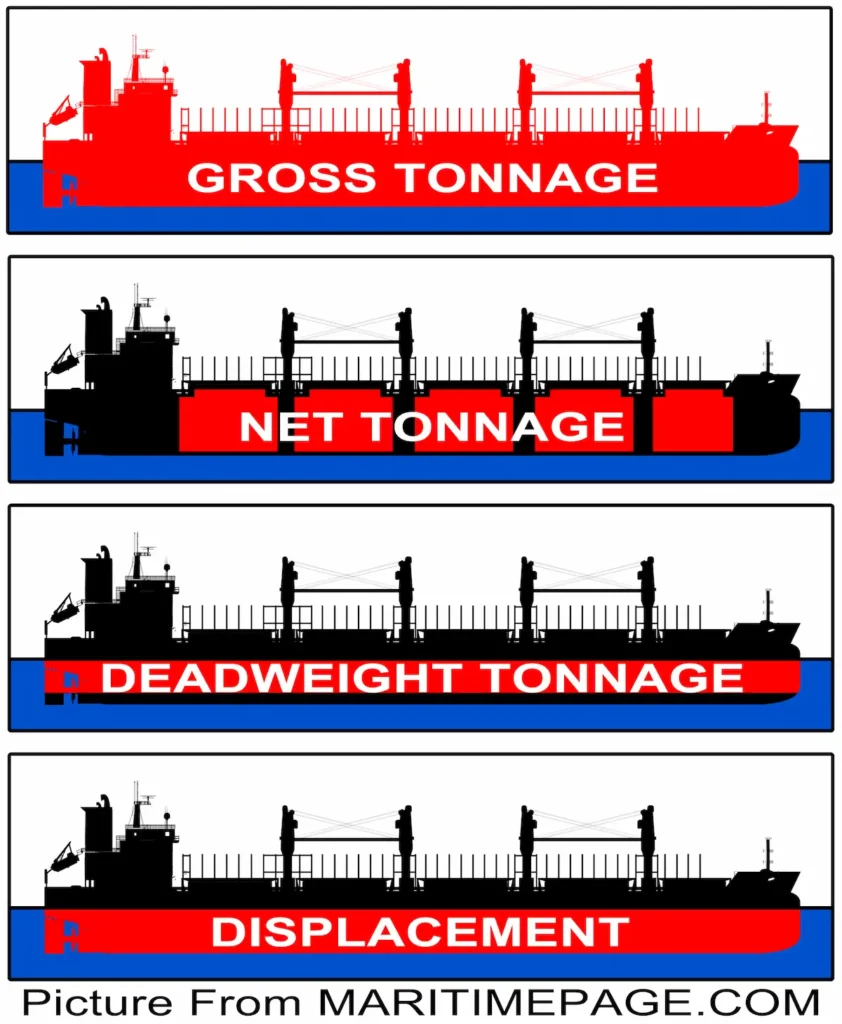

There are five main types of ship tonnage used in the maritime industry: Gross Tonnage, Net Tonnage, Deadweight Tonnage, Displacement Tonnage, and Lightship Weight Tonnage.

Modern tonnage values vary significantly based on ship type. For instance, an Aframax oil tanker might have a deadweight tonnage (DWT) of around 120,000 tons, while a Capesize dry bulk carrier can reach up to 200,000 DWT.

These values help categorize vessels for port regulations and operational purposes. Explore breakdown of oil tanker types and dry bulk carrier classifications for detailed tonnage data across various ship classes.

Types of Ship Tonnage Explained

- Gross Tonnage (GT): Represents the total enclosed volume of the vessel, encompassing all areas within the hull. Primarily used for registration and port fees, GT also serves as a basis for compliance with international regulations on vessel size and capacity.

- Net Tonnage (NT): Measures the volume dedicated solely to cargo spaces, excluding areas like crew quarters and machinery rooms. NT is used to calculate fees based on earning potential, making it crucial for regulatory and tax purposes.

- Deadweight Tonnage (DWT): Represents the weight of cargo, fuel, passengers, crew, provisions, and water, indicating the vessel’s full carrying capacity. DWT is key to loading limits and safety protocols, defining the maximum weight the ship can safely carry.

- Displacement Tonnage: Measures the volume of water displaced by the vessel when afloat, critical for stability calculations and cargo operations. Displacement tonnage includes two types: lightship displacement (vessel without cargo, fuel, or supplies) and loaded displacement (fully loaded vessel).

- Lightship Weight Tonnage: Refers to the weight of the ship’s structure and permanent equipment, excluding all cargo, fuel, and other supplies. This base weight is crucial for assessing buoyancy and stability under different loading conditions.

How is Ship Tonnage Calculated?

Ship tonnage is measured differently depending on the purpose, with gross tonnage and net tonnage being the most commonly used metrics. Below are the two primary formulas:

- Gross Tonnage (GT)

Gross Tonnage measures the total enclosed volume of a vessel. The formula is:

Gross Tonnage (GT) measures the total enclosed volume of the vessel:

$$ \text{GT} = k1 \times V $$

where:

- ( k1 = 0.2 + 0.02 \log(V) )

- ( V ) = total enclosed volume in cubic meters

- Net Tonnage (NT)

Net Tonnage represents the cargo capacity volume of a ship, excluding spaces not used for cargo. The formula is as follows:

Net Tonnage (NT) calculates the cargo volume capacity of the ship:

$$ \text{NT} = k2 \times V_c \times \left(\frac{4d}{3D}\right)^2 + k3 \times \frac{(N1 + N2)}{10} $$

where:

- ( V_c ) = total cubic volume of cargo spaces

- ( d ) = summer load line draught in meters

- ( D ) = molded depth in meters

- ( N1 ) = total cabins for up to 8 passengers

- ( N2 ) = additional cabins

- ( k3 ) = 1.25 \times \frac{(GT + 10,000)}{10,000} )

How Ship Tonnage Affects Ship Construction

Ship tonnage plays a fundamental role in determining a vessel’s construction, influencing the size, structure, materials, and equipment required for safe and efficient operations. Here are several key ways that tonnage impacts ship construction:

- Structural Reinforcement:

- Higher tonnage vessels, such as container ships or large tankers, require reinforced hulls and frames to support heavier loads and withstand the increased stress from carrying high deadweight tonnage (DWT). Shipbuilders often use stronger steel alloys and additional framing in the hull for vessels exceeding 100,000 DWT to enhance structural integrity.

- Stability and Buoyancy Requirements:

- As displacement tonnage (the weight of water displaced by a ship) increases, stability becomes a critical focus in the design phase. Engineers adjust the vessel’s beam (width) and hull shape to ensure it remains stable under different load conditions. For example, tankers and bulk carriers are designed with a broader beam and low center of gravity to enhance stability, particularly when carrying heavy loads.

- Cargo and Space Optimization:

- Net tonnage (NT) dictates the usable volume available for cargo, influencing how shipbuilders design and segment cargo holds. In container ships, for example, maximizing NT requires constructing tiered cargo holds and efficient deck layouts to accommodate as many containers as possible while adhering to safety regulations.

- Regulatory Compliance and Safety Standards:

- Gross tonnage (GT) is essential for regulatory purposes, affecting international safety, environmental, and crewing requirements. Ships over certain tonnage thresholds must meet specific construction standards set by organizations like the International Maritime Organization (IMO). For instance, vessels over 500 GT must be equipped with advanced fire safety and life-saving systems, adding to the construction’s complexity and cost.

- Fuel Efficiency and Hydrodynamics:

- For high-tonnage vessels, reducing fuel consumption and emissions is a priority. Naval architects often employ hydrodynamic techniques, like optimizing the hull shape and using advanced propulsion systems, to increase fuel efficiency. Bulk carriers and large tankers may include bulbous bows or stern flares to reduce drag, thereby conserving fuel despite their large tonnage.

- Specialized Equipment and Load-Bearing Systems:

- Larger tonnage ships necessitate robust cargo handling and load-bearing systems. Heavy-lift vessels, for example, include reinforced cranes and specialized lifting gear to handle high-weight cargo. Similarly, tankers require reinforced pipelines and pumps to manage the substantial liquid loads in compliance with tonnage-specific safety requirements.

Why Ship Tonnage Matters in Modern Shipping

Ship tonnage isn’t just a regulatory measure – it affects shipping costs, environmental impact, and operational efficiency. With tonnage data:

- Shipping lines optimize cargo handling and fuel consumption.

- Ports assess docking fees.

- Governments levy taxes to maintain navigational infrastructure.

How Ship Tonnage Affects Taxation

Shipping companies often pay a tonnage-based tax, where fees are calculated according to the vessel’s gross tonnage rather than business profits. Port dues, such as those in Singapore, are based on Gross Tonnage (GT) to cover services like docking, harbor maintenance, and security.

For instance, ocean-going vessels calling in Singapore incur port dues based on:

- Size of Vessel: Charged per 100 Gross Tonnage (GT).

- Length of Stay: Calculated in 24-hour blocks.

- Purpose of Call: Categories range from cargo loading/discharging to taking bunkers or crew changes.

There are four categories of port dues tariff, each covering a different purpose of call, such as cargo operations, passenger movement, or shipyard repairs. For a detailed breakdown, refer to the Singapore Port Dues Tariff and our guide on port costs, dues, and fees.

Tonnage Certification: Who Issues It?

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) requires ships to carry an International Tonnage Certificate (ITC). Calculated by the vessel’s classification society and issued by the flag state, this certificate ensures compliance with global safety and manning standards.

Historical Development of Ship Tonnage

The concept of ship tonnage dates back to 1303, when King Edward I introduced a tax based on a ship’s tonnage, which measured a vessel’s capacity in “tuns.” This early metric laid the groundwork for future tonnage calculations, with King Edward III refining it in 1347 by taxing imported wine based on a “tun” (252 gallons or 1,016 kg), thus establishing what is now known as the long ton (2,240 lb).

By the 17th century, Britain formalized ship tonnage measurement with the Builder’s Old Measurement (BOM). BOM calculated tonnage using ship dimensions, specifically length, beam, and depth, making it an essential metric for estimating a vessel’s cargo capacity. However, this method had limitations in precision, especially as international trade and maritime regulations expanded.

Evolution of Tonnage Measurement Methods

In 1854, George Moorsom developed a more accurate system to calculate tonnage, which focused on the volume of a ship rather than just its dimensions. Known as the Moorsom System, this method became the basis for Britain’s first British Shipping Act (1854), introducing terms like gross registered tonnage (GRT) and net registered tonnage (NRT). The emphasis on volume allowed for a fairer system to calculate port fees and registration costs.

For smaller vessels, the Royal Thames Yacht Club introduced the Thames Tonnage in 1855 as an alternative measurement for yachts and similar crafts. Both the Moorsom System and Thames Tonnage gained traction internationally, though nations often modified them to fit their own standards, causing some discrepancies.

International Standardization of Ship Tonnage

International efforts to standardize tonnage began in 1925. However, full standardization only materialized with the IMO International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships (1969), establishing a global metric for tonnage calculations. The convention:

- Replaced GRT and NRT with Gross Tonnage (GT) and Net Tonnage (NT).

- Became effective for new ships on July 18, 1982, and for all ships by July 18, 1994.

- Applied to most vessels, excluding warships, vessels under 24 meters, and certain inland vessels.

This convention marked a significant step in global maritime regulation, ensuring consistency in tonnage calculation and fees across international waters. Today, these standards facilitate more equitable taxation, safety compliance, and port services worldwide.

- Types of Gas Carriers as per IGC Code – April 22, 2025

- Wind-Assisted Propulsion Systems (WAPS): A Game Changer for Maritime Decarbonization – February 6, 2025

- 10 Boat Salvage Yards in California – January 25, 2025