The backbone of Global trade is the need to transport goods safely, efficiently, and cost-effectively by avoiding delays in ports and optimizing the combination of the different modes of transportation. Because containerization satisfied these needs it has now become the major means for transporting goods and materials around the world.

Containerization is a system that uses standard containers for freight transport according to standards set out by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

Container ships are cargo ships that carry all of their load in truck-size intermodal containers, in the technique called containerization.

The ISO 668:2020 contains provisions that specify the standards for intermodal containers. In this write-up, we will explore the history of container ships and how they evolved and shaped the maritime industry. We will also discuss the various types of container ships and their features. So, if you’ve ever wondered what container ships are and how they work, read on!

What Are Container Ships Used For?

A container ship is a large, specialized vessel designed to carry containers that are loaded with cargo. They are distinguished from other types of vessels by their box-like structure, which consists of a large, weather-tight hold with hatches on the top deck for loading and unloading, and a superstructure containing the ship’s accommodation, bridge, and cargo-handling gear.

Container ships typically have a capacity of between 3,500 and 7,500 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU), with the largest ships capable of carrying more than 21,000 TEU.

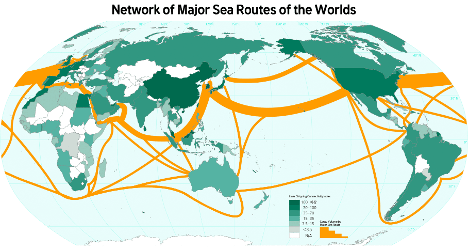

The vast majority of container ship traffic is on routes between Asia, North America, and Europe, although container ship services are also operated between the other continents. Four major container shipping routes ships use. These are:

The North Atlantic route links Western Europe to North America and has the highest traffic volume in the world, accounting for more than two-thirds of the world’s total in terms of both the number of ships and the cargo volume.

The South Atlantic route connects Western Europe to South America. Along this route, agricultural and livestock products from South America, such as wheat, meat, and wool, are traded for industrial goods from Europe.

The Pacific Route has two routes in the North Pacific: the northernmost route in the North Pacific passes near the Aleutian Islands, and the southern route in the North Pacific passes through Hawaii. The South Pacific Route connects the west coast of North America with countries in Oceania such as Australia and New Zealand via the Pacific Ocean.

The European-Asian Route is a sea route that connects Europe to East Asia via the Indian Ocean and, in most cases, via the Suez Canal. If a ship cannot navigate the canal safely it must go around the Cape of Good Hope.

Major Container Ship Routes

The Arctic Route is a sea route from Asia to Europe via the Arctic Ocean. This route is segmented into the Northeast Passage, which links Asia to Europe through waters that are controlled by Russia, and the Northwest Passage, which links North America to Europe through waters that are controlled by Canada.

The Arctic Route, which travels through the Arctic Ocean rather than the currently utilized route that goes through the Suez Canal, has the advantage of significantly reducing the amount of time required for the journey as well as the costs associated with the logistics involved.

It is anticipated that the utilization of the Arctic Route will increase as a result of the reduction of sea ice caused by global warming and the ongoing development of ice-breaking technology.

What Drove the Containerization Revolution?

The containerization revolution was a pivotal moment in the history of international trade. The introduction of the ISO container in the early 1950s changed the way goods were transported around the world, making it quicker and easier to load and unload ships.

This innovation helped to drive the growth of global trade and commerce, as businesses were able to ship larger quantities of goods more efficiently.

The containerization revolution was spurred by the need for a more efficient way to transport goods. Before the introduction of the ISO container, most goods were transported loose or in small containers, such as boxes, bags, or barrels.

This was often time-consuming and expensive, as the majority of the time and cost were associated with loading and unloading the ship. By creating a uniform box that could be easily loaded onto a ship, the containerization revolution solved this problem.

This made it quicker and easier to transport goods around the world, driving the growth of global trade and commerce. Today, the ISO container is the most widely used type of container for shipping goods around the world. Over 60% of the world’s goods are transported using ISO containers, and this number is only expected to grow in the future.

The ISO Container Standards directly drove the containerization revolution, because they dealt with issues for packaging, stowage, loading, and discharging challenges as well as route selection both of which impact on time and cost of shipment.

The standard for example dealt with provisions that were specially designed to facilitate the carriage of goods, by one or more modes of transport, without intermediate reloading; which goes to the core of intermodalism, the transfer of cargo from one mode to another without devanning at the modal interface.

This concept of modal continuity enhances the economic performance of a transport chain by using modes most productively and is perhaps probably the concept that revolutionized global trade.

Then the provisions in the standards also provided for containers to be fitted with devices permitting their ready handling, particularly their transfer from one mode of transport to another, and so designed as to be easy to fill and empty, and, stackable – address the use of standard loading/discharging methods and equipment that facilitate easier and less time-consuming methods of handling. In this way, goods that might have taken days to be loaded or unloaded from a ship can now be handled in a matter of minutes.

Because the maritime transport sector is the mode most constrained by the time taken to load and unload vessels it had to be the sector from which intermodalism should originate with the invention of the container which has since then spread to encompass the other modes. Thus the ability to use standardized ISO containers was a big boon to international trade.

A Brief History of Container Ships

The first container ship was operated by Malcolm McLean’s Sea-Land Service, which began service between Newark, New Jersey, and Houston, Texas in 1956.

The container ship revolutionized maritime transport, as it allowed for the rapid and efficient loading and unloading of cargo, and greatly reduced the amount of time and labor required for loading and unloading ships.

The US military used containerized shipping during the Korean War to stack artillery and other supplies easily on ships and at ports. In 1968 containerization was formally adopted as a standard by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

Since then, there has been a continuous evolution in containership technology, culminating in the latest generation of vessels which are now able to carry unprecedented levels of cargo around the globe quickly, safely, and affordably

Evolution of Containerships

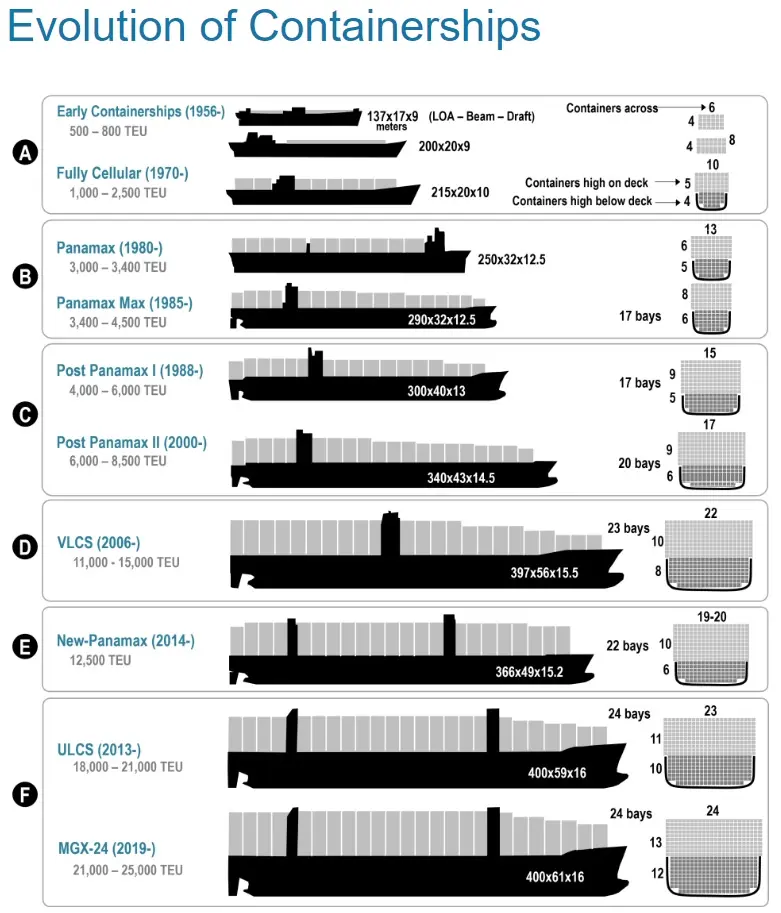

Over the past two decades, the capacity of container ships has tripled and shipyards now have vessels that can hold 24,000 TEUs. In 2006, with the introduction of Emma Mærsk, the first very large container ship (VLCS) went into service. Bigger container ships reduced the cost per TEU even further, which increased demand and therefore incentivized even larger ships.

A containership’s class is determined by its draft and associated TEU capacity. Since containerization started in the middle of the 1950s, containerships have undergone six major waves of change, each of which corresponds to new generations of containerships. The six classes have been:

- Early containerships

- Fully cellular container shops

- Panamax

- Panamax Max

- Post-Panamaxmax I and II

- Very Large Containership (VLCS)

- New-Panamax, or Neo-Panamax (NPX)

- Ultra Large Containership (ULCV)

- Megamax-24 (MGX-24)

The first generation of containerships consisted of bulk carriers or tankers that had been modified to carry up to 1,000 TEUs. They were followed by the Panamax class which was built to fit into the Panama Canal and had a capacity of 4000 TEUs.

By 2006 the Very Large Container Ships (VLCS) made their debut with capacities between 11000 – 14500 TEUS. Maersk introduced Emma Maersk (E class) at this stage which became so popular in media that LEGO designed and started sales of the Maersk E class Lego ship set.

In 2019 ships of 24 containers across 24 bays, dubbed Megamax – 24 were introduced. These vessels are almost getting to the limit of the Suez Canal and are operating on Asia–Europe routes.

What is evident is that each generation of container ships faces a shrinking number of ports able to handle them and places pressure on ports to provide adequate infrastructure to service them. So, about 10 years later, ultra-large container ships (ULCS) with capacities of over 20,000 TEUs are now in existence.

The biggest container ship in terms of capacity in 2022 is the MSC Gülsün, with 24.756 TEUs, 400 meters in length, 61,5 meters in width, and 16,5-metre draught. Even though capacity has risen notably, the size of the newest container ships hasn’t changed that much in recent years.

Container Ships Sizes And Classes

Container ships are categorized into 7 size categories: small feeder, feeder, Feedermax, Panamax, Post-Panamax, New Panamax, and ultra-large. The size of a Panamax vessel is restricted by the Panama Canal’s original lock chambers, which can accommodate ships with a beam of up to 32.31 m, a length overall of up to 294.13 m, and a draft of up to 12.04 m.

The Post-Panamax category typically describes ships with a breadth over 32.31 m, although terminology has changed with the Panama Canal expansion project. The New Panamax category is based on the maximum vessel size that can transit a new set of locks that opened in June 2016.

This new set of locks accommodates a container ship with a length of 366 meters, a maximum width of 49 meters, and a tropical fresh-water draft of 15.2 meters. These ships called the New Panamax class, are wide enough to carry 19 columns of containers and can have a total capacity of approximately 12,000 TEU.

Container ships under 3,000 TEU are known as feeder ships or feeders. They typically operate between smaller container ports and may collect their cargo from small ports, drop it off at large ports for transshipment on larger ships, and distribute containers from the large port to smaller regional ports. This size of the vessel is the most likely to carry cargo cranes onboard.

Here is a table summarizing the various size categories of container ships and their corresponding capacities, and examples:

| Container ship size categories | Capacity (TEU) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Small feeder | Up to 1,000 | MV Beate |

| Feeder | 1,001–2,000 | MV Calisto |

| Feedermax | 2,001–3,000 | MV TransAtlantic |

| Panamax | 3,001–5,100 | MV Providence Bay |

| Post-Panamax | 5,101–10,000 | MV Hyundai Respect |

| New Panamax (or Neopanamax) | 10,000–14,500 | MV COSCO Guangzhou |

| Ultra Large Container Vessel (ULCV) | 14,501–21,000 | MV Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller |

| Megamax-24 (MGX-24) | 21,000–25,000 | MSC Irina, MSC Loreto |

How Do Container Ships Work?

Container ship capacity is measured in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU). Typical loads are a mix of 20-foot (1-TEU) and 40-foot (2-TEU) ISO-standard containers, with the latter predominant.

When a manufacturer receives an order to export he procures a container, brings it to where he has the cargo, and loads the container, making sure the cargo is properly secured inside the container to prevent it from shifting inside the container. The container is brought to the port by a trucking company. Bringing containers to the port or from the port is called “drayage”.

The most common containers are 20-foot dry and 40-foot dry containers examples shown above. There are also refer (refrigerated), high cube, 45-foot, flat racks, open top, open side, liquid, and many other specialty containers available for every conceivable cargo load. The container is kept at the port in the container stacks until the designated ship arrives.

During the loading, a container gantry crane attaches to the container using a spreader and lifts it off the truck. This allows the container twistlocks which are used to lock the containers together to be inserted into slots in the container corner castings.

Basis the cargo plan which nowadays is prepared ashore and confirmed by the ship chief officer the container might be loaded under the deck (in the cargo hold) in which case the container slides into the hold via a cell guide which acts both to secure the container in place and also guides it into its slot.

For above deck stowage, the containers are fitted with twistlocks and stacked on top of each other ensuring that heavier containers are loaded at the bottom of the stack with care being taken not to exceed the stack weight of the deck.

After loading the twistlocks are locked (automatically for semi-automatic and fully automatic twistlocks) lashing bars and turnbuckles are attached and tightened. There is a cross pattern for every box from the deck to the bottom of 2nd tier along the complete row.

There is an additional pattern of lashing from the bottom of the 3rd tier to the deck on the end container stack and possibly the 2nd to end container stack.

In some cases, vertical lashing bars are used on the outer stacks only. Vertical lashing bars attach to the bottom of the third container height and help to increase stack weights. Nowadays to strengthen lashing arrangements a lashing bridge is built between the various bays that ensures that more tiers can be secured by rods.

Once the ship is loaded and the container lashing secured by the Stevedore team the ship can then depart the port. The process is reversed for unloading.

The Benefits of Container Ships

Container vessels have become increasingly popular in recent years, due to their efficiency and cost-effectiveness. They can transport large amounts of goods quickly and efficiently, thanks to their standardization which enables them to be used in any port around the world and within all transport modes.

The economic benefits of containerships include reduced transportation costs, improved shipping times, ie quicker turnaround times, and increased capacity. Containerships are also eco-friendly, as they emit fewer greenhouse gases than traditional cargo ships.

Because containers have many different applications, including the transportation of commodities (such as coal and wheat), manufactured items, automobiles, and perishable goods that need to be refrigerated containerships provide flexibility in goods transportation.

Dry freight, liquid cargo (such as oil and chemical items), and refrigerated cargo each have their specialized container options. In addition, containers that have been thrown away, for example, can be recycled and utilized for a variety of other uses.

The container also functions as its storage and safeguards the goods it carries inside. Because of this, the packaging for containerized cargo, particularly consumer items, will be required to be less complicated and less expensive.

The ability to stack containers more efficiently aboard ships, trains (via double-stacking), and on land (through container yards) is a significant benefit of containerization. A container yard can achieve a higher stacking density by making use of the appropriate equipment.

The Challenges of Container Ships

Despite all these benefits, containership operations do have some drawbacks. The fact that containers require a lot of terminal space necessitates many intermodal terminals to be located on the outskirts of cities implying issues with the transfer of containers to port areas that might need to pass through congested cities.

With the arrival of larger containerships, especially those of the post-Panamax class, draft difficulties at the port are beginning to surface. A post-Panamax containership needs at least a 15-meter draft.

In addition, infrastructure and machinery for handling containers, such as huge cranes, warehouses, inland roads, and rail access, are significant capital projects that call for sizable capital resources. The resources of big businesses or financial institutions are needed for this. Additionally, the drive toward automation is making intermodal facilities more capital-intensive.

The complexity of the container layout on the ground and in the modes (containerships and double-stack trains) might also necessitate periodic restacking, which adds to the terminal operators’ expenses and time. The operational management of a load unit or yard becomes more difficult the larger it is.

Then there is the problem with container repositioning. Because many containers have to be moved without their contents as a result of asymmetries in commerce this implies extra costs; it is estimated repositioning accounts for twenty percent of total movements.

Nevertheless, the volume occupied by a container remains the same regardless of whether or not it contains anything. At the global level, the observed gap between production and consumption necessitates relocating containerized assets over considerable distances (transoceanic).

Since their inception, containerships have had a profound impact on global trade Today, they play a vital role in transporting goods all around the world, and as the demand for containerships continues to grow, so too will their economic benefits

The Future of Container Ships.

Container ships have become the backbone of the global economy, transporting everything from food and consumer goods to heavy machinery and building materials The future of the containership industry is therefore of great importance to businesses and consumers alike.

In recent years, there have been significant advancements in container ship technology, which are set to revolutionize the industry in the coming years.

One such innovation is the use of larger vessels, known as mega-ships, which can carry up to 24,000, TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units.) thereby leveraging the benefits of economies of scale.

Mega-ships are more efficient than traditional vessels thanks to their increased size and capacity, meaning that they can transport more cargo for lower costs. This is good news for businesses who rely on container ships for their operations, as it reduces transport costs and helps to keep prices down for consumers.

- Types of Gas Carriers as per IGC Code – April 22, 2025

- Wind-Assisted Propulsion Systems (WAPS): A Game Changer for Maritime Decarbonization – February 6, 2025

- 10 Boat Salvage Yards in California – January 25, 2025